By Shane Lin, Scholars’ Lab, University of Virginia Library

- What is Git?

- Version control for Digital Humanists

- A Brief History of Version Control

- Git and Github

- Installing Git

- Getting started

- Creating/Cloning a Repository

- Stage and Commit

- Synchronization

- Merging

- Refactoring

- Slightly more advanced concepts

- Panic

- Cheat Sheet

- Credits

- Notes

What is Git?

Git is a popular third-generation Version Control System.

Well okay then! What is version control?

Version control is software that helps many different people work on the same project together without getting in each others’ way. VCS keeps code (and other data) in one place and enforces rules for how it’s updated so everyone can work on the same source simultaneously without risk of overwriting or breaking it. In addition, VCS saves all the different versions of code (and other data) and metadata about each revision. Open source software pioneer and famous misogynist Eric Raymond describes these three capabilities of version control as concurrency, reversibility, and annotation.2 Let’s take a look at what these features are and why they’re useful before diving deeply into how git accomplishes each.

Concurrency

Concurrency allows many different coders to work on the same files at the same time. Doing this and ultimately producing a consistent result is hard. Even with the help of a VCS, it can be a bit of work. Without a VCS, it’s a hot mess. Let’s take a look at a simple example: Alice and Bob are both working on the same file. Alice works all day and saves her changes. Then, without realizing it, Bob saves his changes over hers. Alice gets mad at Bob and their partnership is dissolved in bitterness and enmity.

To get around this, people might coordinate beforehand on what they’ll be working on to stay out of each others’ way. Or they’ll try to label files uniquely, creating many different versions like “code_alice_july_20_c.py”.

But these are onerous workarounds. They often leave Alice and Bob open to more nuanced and insidious problems and they quickly break down as projects become more complex and teams grow larger. Ruby on Rails, one of the largest projects hosted on Github (more about that later), comprises more than 62,000 commits from over 3300 contributors.

Rails is a good example of the power of version control. Software like Git have allowed software development projects, particularly modern open source projects, to leverage the insights and labor from complete strangers from all over the world. There’s a small, core team that has contributed tens of thousands of lines of code, but tens of thousands who have added a few new lines or a tiny bug fix. Scholarship may often be a lonely endeavor, but version control has made it possible for software development to grow into huge parties.

Reversibility

A VCS keeps a record of every revision. This is most commonly useful when things completely fall apart and the ability of reverting to an earlier, good version provides a quick and easy fix. Since we can also see exactly what’s different from version to version, it’s also easy to track down exactly what changes caused the problem. No less useful is the ability to return to an earlier state of the project’s source, to track down a new bug in a specific older version or else to compare the function of new and old code.

Annotation

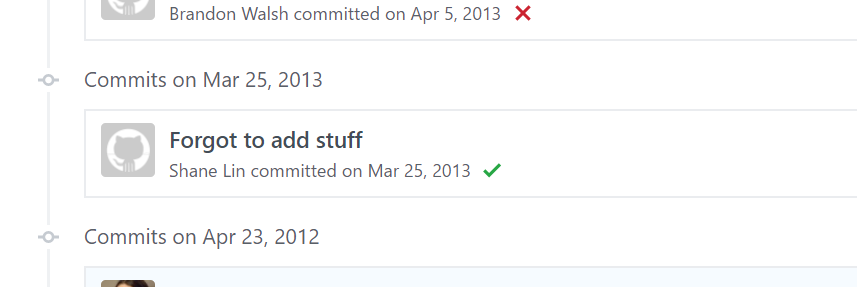

To differing degrees, VCSes also provide ways to manually and automatically describe changes. Whenever Alice and Bob commit a change, they are also required to document what that change does. This feature is useful only insofar as the descriptions illuminate. “Bug fix” or “new feature” are examples of low effort, extremely common, but intellectually vacant comments.

Independent of human fallibility, VCSes also track data automatically. Each commit is tagged with the person who committed it, so that praise or blame can be meted out accordingly. Depending on the system, a VCS may also record the history of a commit such that the entire intellectual lineage of source code can be traced.

In the imaginary field of the intellectual history of software, the metadata and text reserved by VCSes render them as important archives of how ideas in code clashed, branched, and merged.

Version control for Digital Humanists

VCS is predominantly used in software development. Most tools that VCSes integrate with or are integrated with VCSes are designed to carry out development tasks: building, testing, deployment. Trivially, digital humanists who code can take advantage of these usages. However, VCSes can be used with files other than source code.

For scholars collaborating on an essay or book or even a single researcher working alone, a VCS can offer many of the advantages to text it does for code. Working with simple human-readable plain text format rather than binary (legacy Word documents) or heavily formatted (post 2007 Office Open XML Word documents) files will allow users to fully take advantage of a VCS. Markdown, created by John Gruber and Aaron Swartz, is a simple text markup language that’s become the defacto standard in this domain. This page was written in a Markdown flavor.

Software development used to be a solitary or small-scale activity. Version control has changed that dramatically in the last three decades. I don’t know what sort of collaborative possibilities VCS might offer to scholars, but the potential for any kind of radical transformation should merit some thought and experimentation.

A Brief History of Version Control

(I am a cultural historian of computer technology and therefore obliged by the strictures of my guild to include this section. It is not essential to learn how to use Git, but it’s useful to know how it differs from its antecedents. If you are also a cultural historian of computer technology, you are similarly obliged to read this. If you are not, please feel more than free to skip to the next part.)

First Generation

Although there were earlier versioning systems, Marc Rochkind of Bell Labs established many basic concepts of modern version control with the Source Code Control System in 1972. Direct descendants of SCCS survived through the 1990s and its versioning nomenclature, with major and minor version numbers separated by a period, remains popular. It was the progenitor of what Eric Raymond termed the first generation of VCS, characterized by centralization (SCCS was written for the IBM OS/360 mainframe operating system and later adapted to Unix and originally had no network functionality) and simple single-file locking-based concurrency. When Alice wants to do some work, she logs onto the mainframe, locks one file, and the system simply prevents Bob from working on that same file.3

SCCS was followed by the Revision Control System, written by Walter Tichy of Purdue University in 1982. RCS was functionally very similar to SCCS (centralized, locking-based) and was, like SCCS, originally offered with a restrictive proprietary license.4 However, Tichy began to loosen these restrictions over the next decade and, in 1990, released version 4.3 under the GPL. RCS became an important part of the early Free Software movement, eventually falling under the auspices of the GNU Project. As a result, unlike SCCS, it remains maintained, widely available, and still in modest use.5 Version control systems of this generation were and still are best used for simple code without complex structures (e.g. single file scripts, text files) by very small teams. RCS has survived for so long because its simplicity makes it easy to use for trivial versioning.

Second Generation

The next generation of version control was created to accommodate more complex programing structure and to leverage the increasing power of computer networks. Dick Grune, a lecturer at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam, wrote a series of wrapper scripts for RCS in the mid-1980s that eventually became the Concurrent Versions System.6 CVS’s major advance was to switch to a merging rather than locking-based approach to synchrony, which allowed users to work simultaneously and still arrive at a consistent final state. Additionally, CVS supported TCP/IP connectivity by the mid-1990s, in time for the first big wave of Internet adoption. With these features, CVS enjoyed unparalleled success for a decade.

By the late-1990s, programmers became increasingly aware that CVS’s poor support for fileset operations, inherited from the file-based operation of its RCS predecessor, posed a major problem. CVS fileset commits were not atomic and could leave a fileset partially commited if errors were encountered. Subversion, a VCS developed explicitly to replace CVS by a team comprised of former CVS developers, was released in 2000. Its interface is designed to mimick that of CVS, but offered more robust fileset support with atomic commits. Within a few years, Subversion succeeded in winning over most of the CVS community.

Third Generation

Subversion’s success was relatively short-lived. Within a few years of its release, the next generation of decentralized VCS began to gain influence. Larry McVoy’s BitKeeper was designed explicitly to comport with the distributed, “patch-oriented” style of Linux kernel development, the highest profile open source project of its day. BitKeeper, along with Arch, also popularized the shift from filesets to changesets that further made operations like branching even lighter weight. However, due to a variety of issues, ranging from a lack of functional maturity and performance problems to licensing issues, no decentralized VCS had significant adoption over the long-term until the release of Git, which seemed to adequately solve each of these concerns.

Since then, Git has become very, very widely used.

Git and Github

Git is a third-generation version control system. Github is the most popular web-based code repository that uses Git.

Git was created in 2005 by the creator of the Linux kernel, Linus Torvalds, for use in its development. Torvalds designed Git to be a repudiation of the core design of CVS; it is a distributed, commit-before-merge VCS that better supports massive projects and easy non-linear development through rapid branching and merging.7 At least in theory. It is Free Software licensed under the GPL. The name “Git” comports with its description as “the stupid content tracker.”8

Github is a company and a website that couples online Git repositories with social features to promote collaborative open development. In June of 2017, Microsoft reached an agreement to purchase Github.9 It is the largest such source code hosting website with tens of millions of users. It was built with Ruby on Rails, a project it also hosts. Most of Scholars’ Lab’s code lives on our Github account and the service is popular with other Digital Humanists. Github’s mascot is, for some reason, the Octocat, a chimera with a human face, a felid head, and (despite the name) only five tentacles.

Installing Git

Since we’ll be using Git with Github, create a free account at Github now: https://github.com/join?source=header-home

Github provides a graphic interface front-end to Git called Github Desktop, for use with their services. Some other IDEs also have built-in integration with Git. Instead of using these, we’re going to do this the “hard” way using the command line so that we know exactly what’s going on every step.

Linux

If you’re using a Debian-based distribution like Ubuntu, install git using the APT package manager. Open the terminal using the Ctrl-Alt-T shortcut and type: sudo apt-get install git

If you’re using some other kind of *nix, take a look here: https://git-scm.com/download/linux

Verify that the installation has succeeded by typing: git --version

OSX

For OSX version 10.9 (Mavericks) and above, the easiest way is to open the Terminal app and type git. If you don’t have it installed already, OSX will prompt you to install XCode, which comes bundled with an Apple fork of Git.

Alternatively, download the OSX binary installer for the latest stable release from http://git-scm.com/download/mac.

Verify that the installation has succeeded by typing: git --version

Windows

Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL) is a good piece of software. If you use WSL, you can follow the Linux instructions above.

To run git natively, download the Windows binary installer for the latest stable release from https://git-scm.com/download/win.

Default settings should be fine. Once the installation is complete, open the special Git Bash terminal. This uses MinGW-w64’s Bourne Shell command line interpreter which supports the same POSIX shell commands native to the Linux and OSX terminals. If you’re familiar with the DOS style command line, most of the commands are different but the functionality is similar.

In this shell, verify that the installation has succeeded by typing: git --version

Getting started

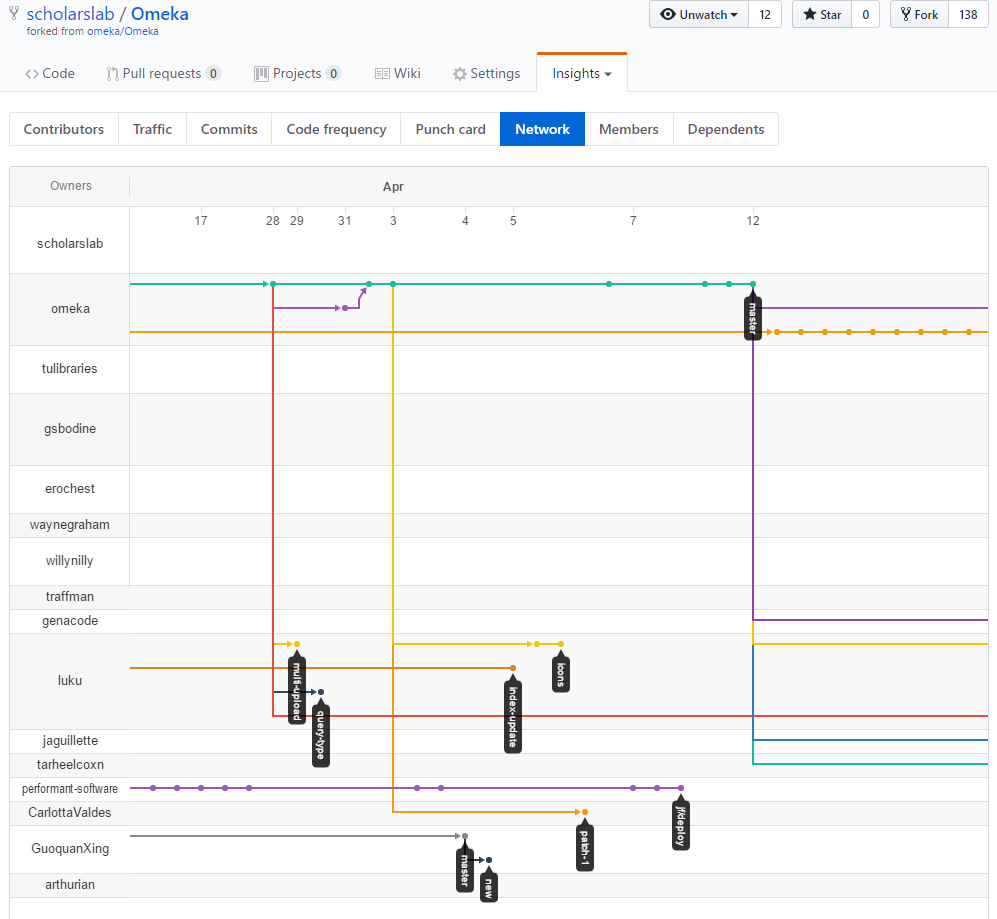

A repository is the data store that contains all the files that git manages. Unlike earlier, centralized repositories that stored files in a single central server, Git repositories are distributed. Each user has a local repository of his or her computer. Actually, everyone can have many repositories. The common practice is that a new repository is created for every distinct project. A single central repository might serve as the authoritative source for a project, but local repositories allow users to work disconnected from it and still enjoy the benefits of VCS.

Repositories can be created from scratch or else cloned from another. Git’s decentralized system means that the typical workflow for checking out code, making changes, and then submitting those changes is to essentially fork a remote repository (from, say, Github) to your local one, make changes, and then merge those changes back to the remote. In the last generation of VCSes and past understanding of software development, forking had a tone of permanence, implying a cleft that is difficult to rejoin. In Git, forks and branches are often described as “lightweight” and constantly created, diverged, and converged.

When you create a new repository in a directory with Git, it creates a hidden .git subdirectory that stores all its additional data. Otherwise, the current version of files tracked by the repository live in the directory normally, able to be directly edited, compiled, and otherwise used.

Creating/Cloning a Repository

To create a new repository, navigate to a directory and type: git init

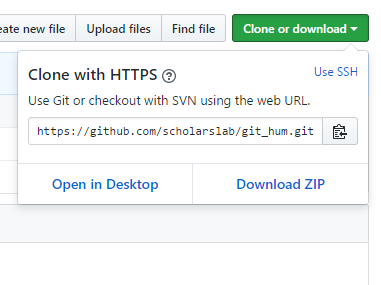

But normally, especially if we’re using Github, this isn’t necessary. Usually, we’ll want to create our repositories on a remote server first and then clone them locally. To do this, create a new repo on your account on Github (or fork another repo) by clicking the green “new repository” button or through the + menu on the top right menu.

In the Github page for the new repository, click the green “Clone or download” button and copy the URL that pops up. Paste that url into this terminal command: git clone *url*

This will create a new local repository in a new directory under the current path with the name of the repo. And that’s it. Now you’ve got two Git repositories up and running: the remote one on Github and the local one in the directory you chose.

Switch to that new directory and check how the repo is doing with: git status

This is a useful command that tells you what branch you’re on, what changes you have staged (or not), where your local repo is relative to the remote, and some warnings and errors with your configuration.

You can also take a look at the entire history of the repo with git log

Stage and Commit

Let’s make some changes. Create a new file in the directory: touch foo.bar

Try git status again. Git should recognize that there’s a new file, but since we haven’t explicitly told it to care about that file, it’s still an “untracked file.”

This file and whatever other changes we might have made now exist as part of our “working tree”, the set of files that we’re currently working on, but aren’t yet stored into the repository. To store a file into the repository, we have to commit it and before we can commit a file, we need to track and stage it.

We can tell Git to track the new file using git add foo.bar or simply git add --all to add all the files in the directory. By default, git add * still ignores temporary, build, and log files that are typically generated by the compilation and running of source code, which we almost never want version control to track.

git add also stages a file by adding it to the index, which tells git what files we want to commit. A Git commit is the most basic operation that describes how sets of files have changed. Each commit lives forever in the history of the project, uniquely identified by a 40-character hash.

To commit the index, we use git commit -m "message"

All commits require a message that describes the changes. Instead of manually staging them, files that have been changed and are already tracked by Git can be automatically added to the index at the time of commit using the -a flag.

Synchronization

Now, the file is committed to our local repository. But it doesn’t yet exist on the remote. Synchronization in git happens using pull and push commands. These are essentially mirrored commands and which one you use depends on what permissions you have.

Typically, if we have the authority to write to the remote repo, we can use git push origin master

This tells Git to push our changes back to the origin, which is a reference to the remote repo at Github that we cloned ours from, on the master branch, which is the default, main branch (more on branches later). This updates the remote repo with our changes.

Merging

What if two people are working on the same project? Alice and Bob both clone the same remote repo. Alice finishes her work first, commits her changes, and then pushes those changes back to the remote. Bob finishes his work, commits his changes, and then runs git push origin master

In this case, Git returns a rejection and helpfully tells Bob that he needs to do a pull first. This happens even if Bob and Alice have edited different files, because source code is so heavily interdependent.

A Git pull is the opposite of a push. By running git pull origin, we’re pulling the changes that have been made to the remote server back to our local repo.

Sometimes, the changes that we’ve made and the ones we’re pulling aren’t in conflict and Git is able to just magically merge them automatically (usually correctly, very occasionally catastrophically). Other times, the two sets of changes do conflict and it isn’t obvious to Git how to resolve the impasse. In these cases, it notes the conflicts in the files and leaves it to the user to fix them.

Once the conflicts have been manually resolved, mark the files as ready for commitment with git add

Refactoring

We’re (maybe?) used to working with the command line to perform basic operations on files. When working with version control, instead of using the terminal/shell to move or delete files directly, using the analogous git commands git mv foo.bar foo.bar2 and git rm foo.bar2 will allow git to reflect those changes. This way, deleting local files will also stage them for deletion and moving local files retains their history (otherwise they must be added as wholly new files).

Slightly more advanced concepts

Branches

Git makes it easy to create independent copies of repositories; in VCS-speak, this is called forking. There’s also a similar VCS idea called branching. Branches are like repository forks in that they allow code to diverge, but with a slightly different inflection. Git branches live in repos and they’re all copied over when a repo is cloned. The philosophical distinction between forks and branches used to be clearer. Forks were implicitly permanent divorces and they still possess that tone when used in context of projects rather than version control. There are multitudes of Linux distributions, a majority which have been forked from three lineages: Debian, Slackware, and Red Hat. Once these distributions fork off, instances of two converging again are virtually nonexistant. In contrast, branches stay within the same project and are created with the expectation that they will probably, eventually be reconciled. Yes, this is all metaphorically confusing, since tree branches don’t typically converge whereas roads that fork often do, but some allowance must be made for software engineers. Branching is typicaly used to separate the development of independent features. A common practice is to keep a “production” branch that represents the live code running in the wild and segregate new development onto an array of branches that are only merged back once they’re ready to launch. This makes it easy to develop and deploy bug fixes without needing to temporarily shelve new code.

Git and its generation of VCSes along with Github have really confused the distinction between forks and branches. All local repositories are technically forks, even if, in most cases, cloning a repo is done to work within the project. By taking a “lightweight” approach to forking, git removes the technical barriers to breaking code apart and putting it back together, leaving these decisions entirely to people. The difference between git forks and branches are therefore often more psychological than practical. There are some technical differences (repositories hold full copies of data whereas branches are just pointers to a certain commit), but often these don’t really affect the user experience.

We’ve actually already used git forks and branches. Our cloned repos are forks. When we’ve pushed and pulled, we’ve typically specified a branch after the repository. The default branch in Git is the master branch. We can create a new branch based on the current one using git branch *new_branch*

git branch --list will list out all the existing branches in the repository.

git checkout *branch_name* switches the active branch within a repository. This is very different behavior from how other VCSes use the keyword “checkout.”

Once changes in one branch are ready to be committed back to another, we can use git merge *branch_name* to bring those changes back into the current branch. After that, git branch -d *branch_name* deletes the branch.

Pull requests

One final thing, to shape you all into productive members of society.

Open source software thrives on the limitless collaborative possibilities of the Internet. But the usual case when working with a project someone else owns is that you won’t have permission to push directly to their repository. The polite way to suggest a contribution is the Pull Request, which is exactly what it sounds like - a request asking a remote repo to pull commits from yours.

There’s a way to do this through the command line (git request-pull), but with Github’s titanic popularity and the social and project management features it offers, it’s probably better to go through the Github website for this.

Panic

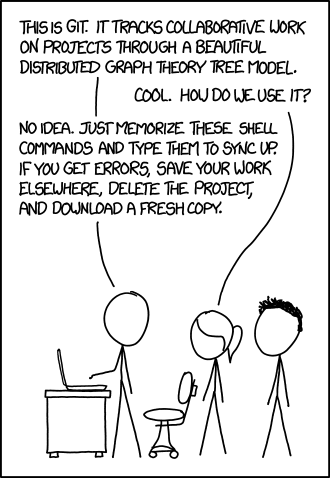

Obligatory XKCD10:

Sometimes everything goes to hell. If you don’t have uncommitted changes you want to keep and a Git operation goes completely off the rails, you can always roll back and try again:

git reset --hard resets the working tree to the last commit, obliterating all uncommited changes (but doesn’t remove untracked files)

git clean -xdf completely removes all untracked files.

Cheat Sheet

Github has a nice Git cheatsheet.

Credits

This page was by Shane Lin using Jekyll. The Theme is Shu Uesugi’s Solo.

This document is offered under the, I guess, the MIT license. Do whatever you want with it, just please don’t sue me.

Notes

-

Thanks to Charles Berlin for the O’rly cover generator ↩

-

Much of the historical material in this guide comes from Eric Raymond’s Understanding Version-Control Systems (DRAFT) ↩

-

The latest version, as I write this, is 5.9.4, released January 2015. https://www.cs.purdue.edu/homes/trinkle/RCS/ ↩

-

Torvalds described the Git design process as “WWCVSND: What Would CVS Never Do”. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4XpnKHJAok8 ↩

-

https://github.com/git/git/blob/e83c5163316f89bfbde7d9ab23ca2e25604af290/README ↩

-

[https://news.microsoft.com/2018/06/04/microsoft-to-acquire-github-for-7-5-billion/] ↩